Varieties of Lynchburg Glass, Part II

by Dennis Bratcher - Oklahoma City, OK

Reprinted from "Crown Jewels of the Wire", August 1986, page 27

Part 2: The CD 112

As noted in Part 1, the Lynchburg Glass Company struggled to show a profit

throughout its short history, in fact, struggled just to break even! One of

Lynchburg's tactics for reducing overhead was to reuse secondhand insulator

molds thus eliminating the considerable expense of designing and tooling new

molds. Of course at the same time this practice provided us collectors with

something to do!

One problem in the reuse of molds was the suitability of the styles of the

available molds for the current market demands. Obviously, Lynchburg was not

going to have ready access to state-of-the-art molds and designs from Hemingray

or Whitall-Tatum, so the company had to make-do with the molds they could

obtain. One of the best examples of their creativity in re-tooling available

molds to meet market demands was the Lynchburg No. 31, CD 112.

The Lynchburg No. 31, although assigned the CD number 112 and broadly fitting

into this design category, is actually a unique design created in the Lynchburg

shops. The style exhibits features of both CD 112 and CD 113 and comes closest

in design to the early Hemingray No. 12, CD 113, although minus the top lip on

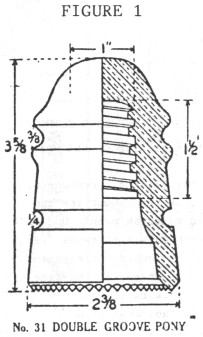

the upper wire groove. In fact, on a mailer sent by Lynchburg to prospective

customers to illustrate their line of insulators, an illustration of a Hemingray

No. 12 was used to depict the Lynchburg No. 31. The illustration, as are most in the

mailer, was obviously taken from a Hemingray catalog (a 1921

Hemingray catalog was in the Lynchburg records acquired by Mr. Woodward; see

figure 1).

Illustration of the No. 31

from a Lynchburg Mailer

Since the Gayner company had never produced the double-groove pony

style, and therefore Mr. Gayner could not supply these molds, Lynchburg had to

either acquire or manufacture molds for this style. With the specific configuration

of the No. 31 being unique to Lynchburg, it could be concluded that Lynchburg

manufactured the molds themselves. But the key to their true origin is the crown

top markings which appear on all Lynchburg No. 31s: either numbers, often

backwards, such as "01 or "2" or letters such as "XO"

(or "OX"). Apart from mold numbers, Lynchburg did not use shop

markings on any insulators. The only crown markings used by Lynchburg were the

occasional placement of the oval trademark there (CD 162, CD 121, CD 154) and the style numbers of CD 281 and CD 306. This fact

suggests that the molds are secondhand and the crown markings, especially the

"X0", immediately suggests a Brookfield origin for the molds since this was a

common shop marking used by Brookfield. But Brookfield, even with their three

major varieties of CD 112s (cf. Cranfill & Kareofelas, The Glass

Insulator,

1973, p. 39) and several minor variations, never produced a CD 112 like the

Lynchburg No. 31.

While it is possible that Lynchburg acquired CD 112 Brookfield molds and then

altered them into the Lynchburg design, this is highly unlikely. There would be

little reason for Lynchburg to go to the expense of altering a CD 112 mold in

the minor ways in which the Lynchburg No. 31 differed from the Brookfield No. 31.

It would have been much more economical to simply re-cut the Lynchburg logo over

the Brookfield embossing as was done with the No. 36, CD 162 molds acquired from

Brookfield.

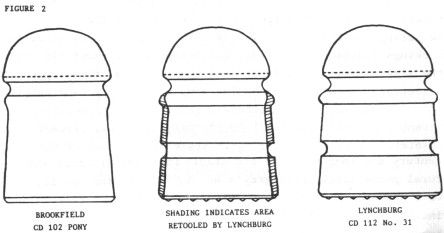

The conclusion at this point is that Lynchburg re-worked another Brookfield

style into the CD 112, No. 31. Comparing the top (crown) 1/3 of the Lynchburg

mold, since the markings indicate it was left unaltered, with Brookfield styles,

the size and nearly hemispherical shape of the crown suggests a certain variety

of the CD 102 pony as a likely candidate.

By the time Lynchburg began insulator production in November of 1923, the

small CD 102 pony style was already obsolete. While a popular early style to the

turn of the century and long a Brookfield staple for short distance and rural

phone lines, Hemingray's No. 9, CD 106, and No. 12, CD 113, were increasingly

popular (due to several factors including Brookfield's war-era problems). By the

time Brookfield ceased production in 1920 the CD 106 and CD 113 were the

standard short line phone insulators. When Lynchburg laid their hands on the Brookfield

molds for the CD 102 they had an obsolete insulator which was

virtually unsaleable. Since they already had an insulator from the Gayner molds

to compete with Hemingray's No. 9 (Lynchburg No. 10, CD 106), they needed a

double groove pony to compete with Hemingray's popular No. 12. So, I suggest,

the Brookfield CD 102 molds were machined to new specifications which yielded

the Lynchburg No. 31, CD 112.

A careful examination of the No. 31 and a comparison with some Brookfield CD

102s supports this conclusion. The slope of the sides of the two are nearly

identical and measurements of the unusually thick middle section of the No. 31 are exactly

what would be required for the CD 102 mold to be retooled to allow the bottom

wire groove on the CD 112 (figure 2). Also an examination of the base of

Lynchburg No. 31s shows that the sides of the insulators extend between 1 and

1.5 mm past the base rim all around the base, a result of the sides of the mold

being machined out into the wider style.

Too, the many minor variations of the Lynchburg No. 31, mostly in the width

and shape of the upper wire groove lip, the size and shape of the crown, and the

height of the insulator (rarely are two different Lynchburg No. 31 molds

identical) would be consistent both with the wide variety of Brookfield CD 102s

and the fact that modifications were being made to existing molds. The

conclusion, then, is that the Lynchburg No. 31, CD 112, is a result of the

modification of the Brookfield Pony CD 102.

The lettering on the Lynchburg No. 31 is, for Lynchburg, amazingly

consistent. The front embossing is usually 7.5 mm high and reads LYNCHBURG No.

31 while the reverse embossing is the familiar "L" in a large oval (13

x 19 mm) followed by the mold number, then MADE IN / U.S.A. in two lines. I know

of mold numbers through nine, although I suspect there may be more. I know of no

embossing errors on the No. 31.

There are two kinds of drip points found on the No. 31. The more common one

is small and cone-shaped slanting slightly inward which would indicate that the

points were added to an originally smooth-based mold. There are always 28 and

are uniform in size. A much scarcer type is a larger drip point that is

cylindrical at the base and rounded at the tip. There are usually only 27 of

these points and are frequently of slightly varying sizes.

I have never seen nor heard of a smooth base No. 31 and doubt if one was ever

produced by Lynchburg. The primary competition was the Hemingray No. 12 which Hemingray widely advertised with drip points as a primary feature.

The Lynchburg No. 31 does not occur in a wide variety of colors due to the

fact that it was only in production a total of eleven weeks (and not every day

in those weeks). The most common color that I have seen is a light sagey

green-aqua. It also occurs in green, a darker near-emerald green and yellow-green as well as crystal clear. I have reports of clear with a pinkish tint and

clear with a smoke tint but I have not been able to confirm these. It also

occurs in a light aqua, although I have not seen the bright sparkling blue-aqua

common to other Lynchburg styles.

The number of No. 31s sold by Lynchburg in such a short time (175,000)

attests to their ingenuity in the modification of obsolete molds.

|